IN THIS LESSON

Topics Covered:

Breast Structure and Function

Learn the anatomy of the breast and how each component contributes to lactation.Hormonal Regulation of Milk Production

Explore the roles of prolactin, oxytocin, and other hormones in milk synthesis and release.The Letdown Reflex

Understand the physiology of milk ejection and factors that influence the reflex.

Introduction

Lactation is a coordinated system of structures, nerves, and hormones working together to make and move milk. In this lesson you’ll learn how the breast is built (alveoli, ducts, myoepithelial cells), how hormones like prolactin and oxytocin turn that hardware “on,” and how effective milk removal keeps the system running. We’ll connect normal physiology to everyday problems—engorgement, low transfer, nipple pain—so you can spot what’s off and choose the simplest fix. By the end, you’ll be able to explain why a deeper latch, skin-to-skin, or timely expression works—not just that it does.

1. Breast Structure and Function

Learning Objectives

Describe the main parts of the breast involved in lactation.

Explain how breast structures work together to produce and deliver milk.

Recognize normal breast changes during pregnancy and postpartum.

Definition & Explanation

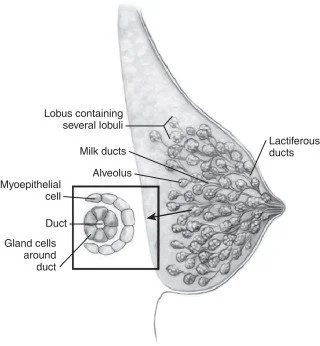

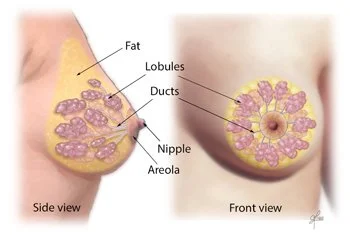

The breast is not just “one organ,” but a system of different tissues working together to produce and deliver milk. The milk-making tissue is organized into lobes, which are like the slices of an orange. Each lobe is made up of lobules, and inside those lobules are tiny sacs called alveoli. These alveoli are the “milk factories” where breastmilk is made.

Milk flows out of the alveoli through small tubes called ducts, which connect to the nipple. Think of ducts as a system of straws that carry milk from where it’s made to where the baby can drink it. Around the nipple is the areola, which contains small glands that release oils to keep the nipple skin healthy and to provide a scent that helps guide newborns to latch.

During pregnancy, hormones like estrogen and progesterone signal the breast to grow more alveoli and ducts. This explains why breasts often feel fuller, heavier, or more tender in pregnancy. After birth, another hormone, prolactin, takes over as the main driver of milk production.

Example: Imagine the breast as a tree. The alveoli are the leaves where “milk” is made, the ducts are the branches that carry the milk, and the nipple is the trunk where everything comes together for the baby.

Scenarios & Tips

Scenario: A parent says, “Why do my breasts feel lumpy when they’re full?”

Response: “That’s normal. The lumps are the milk-filled lobules and alveoli. Once your baby nurses or you express milk, they’ll feel softer.”

Tip: Normalize fullness and changes—help parents recognize what’s expected vs. when to seek help (e.g., painful hard lumps).Scenario: A pregnant parent asks, “Why are my nipples darker than before?”

Response: “During pregnancy, the areola gets darker to help your baby see and find the breast more easily after birth.”

Tip: Use this as an opportunity to explain how the body naturally prepares to guide infants.Scenario: A parent says, “I don’t feel much breast change in pregnancy—should I be worried?”

Response: “Every body is different. Some people notice big changes, while others notice very little. It doesn’t necessarily mean you won’t make milk.”

Tip: Reassure without overpromising, and suggest follow-up if concerns continue postpartum.

Evidence-Based Insights

Recent evidence shows that what matters for milk production is function, not appearance. A large review by Geddes and colleagues reports that measured 24-hour milk production in lactating parents was not correlated with breast glandular tissue estimates, duct number/diameter, or storage capacity—meaning breast size/shape alone doesn’t predict supply. Practically, milk output is driven by effective, frequent removal and the lactation physiology that supports it. This helps families reframe concerns about “small” or “large” breasts and focus instead on latch quality, milk transfer, and feeding patterns. PMC

Another line of research explains why the areola matters for early feeds. In a PLOS ONE experiment, two-day-old newborns exposed to natural secretions from Montgomery (areolar) glands showed stronger breathing and mouth movements than to human milk, formula, or control odors—evidence that areolar scents act like a built-in “guidance system” that helps babies orient and begin feeding. This supports common best practices such as skin-to-skin care, early breast contact, and avoiding strong fragrances on the breast during the early postpartum period so those cues aren’t masked. PMC

Suggestions for lactation specialists

Reassure clients that breast size doesn’t predict supply; center your assessment on latch, transfer, infant output, and feeding frequency/response to demand. PMC

Coach frequent, effective milk removal (direct breastfeeding or well-fitted pumping) as the primary lever for protecting/boosting supply. PMC

In the first days, encourage uninterrupted skin-to-skin and early breast contact; advise avoiding perfumes/strong soaps on the breast to preserve areolar scent cues. PMC

When troubleshooting early latching, use positioning that lets the baby’s nose/cheeks contact the areola (baby-led latch), leveraging innate olfactory orientation. PMC

Key Terms & Definitions

Alveoli: Alveoli are tiny, grape-like sacs inside the breast where breastmilk is made and stored before it is released. These sacs are surrounded by specialized cells that produce milk in response to the hormone prolactin. When the letdown reflex is triggered, the muscles around the alveoli contract and push milk into the ducts. For example, you can think of alveoli as “mini milk factories” working nonstop to produce nourishment for the baby. The number and efficiency of alveoli can influence how much milk a parent produces. They are the starting point of the milk production and flow process.

Lobes/Lobules: Lobes and lobules are groups of alveoli that are organized in clusters, much like the sections of an orange. Each breast has multiple lobes, and inside each lobe are smaller lobules filled with milk-producing alveoli. This organization helps distribute milk production evenly across the breast. For instance, if one lobe is drained well during feeding, the body gets the signal to keep making milk in that area. This structure ensures that milk is available throughout the breast and not just from one part. Understanding this setup helps explain why it is important to switch sides or adjust positioning during breastfeeding.

Ducts: Ducts are the narrow tubes that carry milk from the alveoli, through the breast, and to the nipple where the baby can access it. They function like small pipelines, ensuring that milk produced deep inside the breast can reach the surface. When the milk ejection reflex is triggered, milk travels quickly through these ducts. For example, if a baby unlatches during letdown, milk might spray from the nipple, which is a sign of ducts releasing milk under pressure. Keeping ducts free of blockages is important, since clogged ducts can cause pain or even lead to infection. They are the “delivery system” of breastfeeding.

Areola: The areola is the darker, circular area around the nipple that contains glands and scent markers to guide the baby during feeding. These glands secrete oils that moisturize the skin and help prevent dryness or cracking. Babies are naturally drawn to the scent of the areola, which helps them find the nipple and latch effectively. For instance, even newborns placed skin-to-skin with their parent often crawl toward the breast, guided partly by the scent from the areola. Its color contrast also makes the nipple more visible to the baby. This area plays both a biological and sensory role in successful breastfeeding.

Prolactin: Prolactin is the hormone that drives milk production in the alveoli. Its levels rise after birth and continue to rise every time milk is removed, whether through breastfeeding or pumping. For example, when a baby nurses frequently during growth spurts, prolactin helps the body increase milk supply to meet demand. Without enough stimulation, prolactin levels drop, and milk production slows down. This hormone also contributes to a calming effect, helping parents feel more relaxed during feeding. It works hand-in-hand with oxytocin, ensuring both milk production and milk release.

FAQs: How Breast Structure Supports Milk Production

-

Scenario: A parent notices the left breast feels fuller and pumps more milk than the right.

Answer: It’s very common for one breast to be more productive. Differences in milk-making tissue, duct size, or how baby latches on each side can affect output. Both breasts still contribute to supply. As long as baby is gaining weight well, the imbalance isn’t harmful. -

Scenario: A parent feels small, movable lumps after a feed and worries about clogged ducts.

Answer: After feeding, you may feel small areas of firmness where lobules are located. These usually soften as milk is drained. If a lump persists, becomes painful, or is accompanied by redness or fever, that’s when to get checked. -

Scenario: A parent notices small raised spots on the areola during pregnancy.

Answer: Those are Montgomery glands—normal oil-producing glands that secrete substances to protect the nipple and help guide your baby to the breast. They’re not clogged pores and don’t need to be squeezed or treated. -

Scenario: A parent worries that flatter nipples won’t work for breastfeeding.

Answer: Babies don’t just latch to the nipple, but to the areola as well. Flat or inverted nipples can still work, especially with skin-to-skin, hand expression, and proper positioning. If baby struggles to latch, a lactation consultant can suggest techniques or tools like nipple shields. -

Scenario: A parent with smaller breasts is worried about not having enough milk for their newborn.

Answer: Breast size is determined mostly by fatty tissue, not the number of milk-making glands. Milk production depends on how often and effectively milk is removed, not breast size. Parents with small or large breasts can all make enough milk.

Breast anatomy and lactation

2. Hormonal Regulation of Milk Production

Definition & Explanation

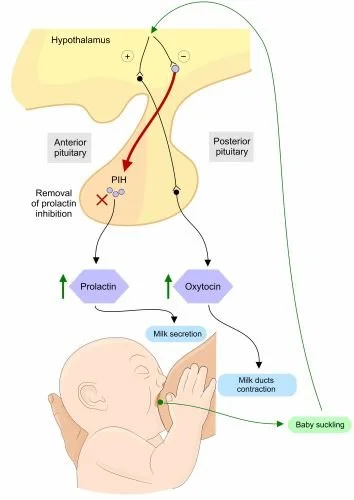

Milk production and release depend on two key hormones: prolactin and oxytocin.

Prolactin is often called the “milk-making hormone.” It tells the alveoli (milk sacs) to produce milk. Prolactin levels rise when the baby suckles or when milk is removed by pumping or hand expression. The more milk is removed, the more prolactin signals the breast to make more—this is why frequent feeding helps supply.

Oxytocin is known as the “love hormone.” It triggers the muscle cells around the alveoli to contract, pushing milk down the ducts toward the nipple. This process is called the letdown reflex (covered in Topic 3). Oxytocin release can be influenced by emotions, touch, and relaxation.

Other hormones—like estrogen and progesterone—play major roles during pregnancy but decrease after birth, allowing prolactin and oxytocin to take over.

Example: Imagine a factory. Prolactin is the manager who tells the workers (alveoli) to produce more milk. Oxytocin is the shipping department that moves the product (milk) out of the factory and into the delivery trucks (ducts).

Scenarios & Tips

Scenario: A parent says, “I’m worried my milk supply is low because my baby is always nursing.”

Response: “Frequent nursing actually stimulates prolactin and helps build supply. Babies often cluster-feed to tell your body to make more milk.”

Tip: Reframe frequent feeding as a normal and healthy sign of hormonal regulation.Scenario: A parent says, “I feel tense, and milk doesn’t come out as easily—why?”

Response: “Stress can block oxytocin, which controls milk release. Relaxation, deep breathing, and skin-to-skin can help.”

Tip: Teach quick stress-relief tools that parents can use before or during feeding.Scenario: A parent asks, “Do I need special foods or supplements to increase prolactin?”

Response: “The most effective way to boost prolactin is frequent milk removal. Foods and teas can support you, but nursing and pumping are the most important drivers.”

Tip: Keep advice evidence-based—encourage demand-driven feeding over supplements as a first step.

Evidence-Based Insights

In a study by Uvnäs-Moberg et al. (2020), researchers conducted a systematic review of how oxytocin and prolactin respond during breastfeeding in human mothers. They found that oxytocin is released in pulsatile bursts in response to infant suckling (with peaks often within minutes), and that a greater number of oxytocin pulses early in lactation was associated with higher milk yield and longer duration of breastfeeding. However, they also observed that stressors (e.g. noise, mental stress) tend to reduce the number of oxytocin pulses during breastfeeding, which could blunt the milk ejection reflex (i.e. the “let-down”) and thereby reduce effective milk transfer (fewer pulses → less efficient ejection). In the same review, the authors noted that prolactin levels also rise during breastfeeding (usually gradually, over tens of minutes) and that oxytocin and prolactin responses are interconnected: oxytocin release seems to help promote physiological states (lower cortisol, calmer autonomic balance) that may support sustained lactation and maternal adaptation. In summary: the “spike after each feeding” claim is partly supported (prolactin does rise in response to feeding), but the relationship is more nuanced (timing, pulsatility of oxytocin matters, and stress can dampen that). (Uvnäs-Moberg et al., 2020) PLOS

A more recent empirical study by Nagel et al. (2021) examined how maternal psychological distress (stress, anxiety, depression) relates to lactation outcomes, and they reviewed mechanistic evidence about how stress may interfere with oxytocin and milk ejection. Their summary showed that higher levels of maternal distress are associated with delayed secretory activation (i.e. later onset of full milk “coming in”) and shorter duration of exclusive breastfeeding. One proposed mechanism is that psychological distress interferes with oxytocin release during infant suckling, thereby impairing the milk ejection reflex. If milk ejection is repeatedly weak or delayed, the breast may not be fully emptied, which in turn can lead to reduced milk production over time (since milk removal is a key driver of supply). They also note that maternal distress correlates with elevated cortisol and metabolic shifts (e.g. insulin resistance) which may have downstream effects on lactation physiology. Thus, the original idea that stress “interferes with oxytocin release” is well supported in this more recent review of human lactation data. (Nagel et al., 2021) PMC

Suggestions for lactation specialists:

Recognize that optimal oxytocin pulsatility and timing matter—not just the presence of hormone rise. Encourage feeding environments that reduce disturbance or anxiety (quiet, calm, supportive) to help maintain robust oxytocin release.

Monitor for signs that let-down is weak or delayed (baby fussing, long pauses before milk flows), and intervene early (positioning, breast massage, hands-on pumping) to assist the reflex.

Screen for maternal psychological distress (stress, anxiety, depression) early in the postpartum period, because elevated distress can impair oxytocin dynamics and thus milk ejection, which over time can affect supply.

Use interventions that support maternal mental well-being (emotional support, mindfulness, counseling referrals, peer support) as part of the lactation care plan—not just focusing on mechanical aspects.

Emphasize frequent, effective breast emptying especially in the first days, because even if hormonal responses are impaired, mechanical removal is still the key driver of maintaining supply.

Key Terms & Definitions

Prolactin: Prolactin is the main hormone responsible for stimulating milk production in the breasts. After birth, when the placenta is delivered, prolactin levels rise, signaling the body to begin producing milk. Every time a baby nurses or milk is removed, prolactin levels increase to encourage more milk production. For example, a mother who breastfeeds frequently will naturally produce more prolactin, helping her body maintain a steady milk supply. This is why consistent nursing or pumping is so important for keeping up with the baby’s needs. Prolactin works behind the scenes, ensuring that the milk supply is always ready.

Oxytocin: Oxytocin is often called the “love hormone” because it is linked with bonding and emotional connection, but it also plays a crucial role in breastfeeding. It is the hormone that triggers the letdown reflex, causing milk stored in the breast to flow out through the ducts. This can happen when the baby latches or even when a parent hears their baby cry. For example, some mothers notice milk leaking at the sound of their baby’s voice—this is oxytocin at work. Beyond milk release, oxytocin also helps the parent feel calmer and more connected to their baby during feeding. This hormone makes breastfeeding both a physical and emotional experience.

Supply-Demand Cycle: The supply-demand cycle describes how the body makes milk in response to how often and how much milk is removed. The more frequently the baby nurses or milk is pumped, the more milk the body is signaled to produce. For example, a parent who breastfeeds on demand (whenever the baby shows hunger cues) will usually have a stronger milk supply than one who schedules feeds and misses baby’s cues. On the other hand, if milk is not removed often, production naturally slows down. This cycle ensures the body does not waste energy making more milk than the baby actually needs. It’s the body’s built-in system for efficiency and balance.

Hormonal Regulation: Hormonal regulation refers to the way hormones control important body functions, including milk production and release during breastfeeding. Prolactin and oxytocin are two key hormones in this system, but others—like estrogen and progesterone—also play roles, especially during pregnancy. For instance, during pregnancy, high progesterone prevents full milk production, but after birth, when progesterone drops, prolactin can fully take over to start milk supply. Hormonal regulation makes sure the right processes happen at the right time to support both the parent and baby. For example, when hormones are balanced, the parent can produce enough milk, feel calm during feeding, and recover after birth. This shows how interconnected the whole body is during lactation.

FAQs: Hormonal Regulation of Milk Supply

-

Scenario: A parent notices milk leaking even before picking up their baby.

Answer: This happens because oxytocin is released when you hear your baby cry, see your baby, or even think about them. Oxytocin contracts the milk ducts and pushes milk toward the nipple, even if your baby isn’t latched. It’s a normal reflex called let-down. -

Scenario: A parent worries because they never feel the “pins-and-needles” sensation others describe.

Answer: Not everyone feels the let-down reflex. What matters most is if your baby is swallowing well, gaining weight, and producing plenty of wet diapers. Those are stronger indicators of milk transfer than physical sensations. -

Scenario: A parent is confused after reading about “two hormones” involved in lactation.

Answer: Prolactin stimulates your breasts to make milk. Oxytocin makes the muscles around the milk glands contract, so milk is released (let-down). Both work together—baby’s sucking boosts prolactin for future milk and oxytocin for immediate flow. -

Scenario: Back at work, the pump yields little the first 5 minutes.

Answer: Use your pump’s let-down mode (fast/light suction) for ~1–2 minutes, then switch to expression (slower/stronger). Watch a baby video, smell a worn baby onesie, or do a 60–90 second warm breast massage before pumping. Correct flange size (nipple moves freely, minimal areola pulled) protects oxytocin release and yield. -

Scenario: Milk leaks during intimacy, while showering, or even at work when thinking about baby.

Answer: Yes, that’s normal. Oxytocin release isn’t limited to feeding—it can be triggered by emotions, sounds, or touch. Wearing breast pads or pressing gently on the breasts through clothing can help control leaking in unexpected situations.

Breastfeeding | 3D Animation

3. The Letdown Reflex

Learning Objectives

Define the letdown reflex and describe how it works.

Identify common sensations and cues associated with letdown.

Recognize normal variations and challenges in letdown reflex.

Definition & Explanation

The letdown reflex—also called the milk ejection reflex—is the process where milk is released from the breast in response to oxytocin. When a baby suckles at the breast, oxytocin causes the muscles around the alveoli to contract, pushing milk through the ducts and out the nipple.

Parents often describe letdown as a tingling, warmth, or tightening in the breast, but not everyone feels it. Some may notice milk leaking from the other breast or dripping without nursing. The letdown reflex can also be triggered by emotional or sensory cues, such as hearing a baby cry or thinking about the baby.

Example: Think of letdown like turning on a faucet. The water (milk) is already there, but oxytocin turns the handle so the milk flows.

Scenarios & Tips

Scenario: A parent says, “I leak milk when I hear another baby cry—is that normal?”

Response: “Yes, that’s your body responding to a cue. Your brain releases oxytocin, which triggers letdown.”

Tip: Normalize these experiences to reduce parent worry.Scenario: A parent says, “I don’t feel any tingling—does that mean I’m not having letdown?”

Response: “Not everyone feels letdown. If your baby is swallowing and gaining weight, your letdown is happening even if you don’t feel it.”

Tip: Focus on baby’s feeding cues instead of sensations.Scenario: A parent says, “My milk sprays out really forcefully and my baby coughs.”

Response: “That’s called overactive letdown. It can be managed by nursing in a laid-back position or letting the initial spray flow into a cloth before latching.”

Tip: Offer practical positioning advice to ease feeding.

Evidence-Based Insights

In the study “Comparison of maternal milk ejection characteristics during pumping using infant-derived and 2-phase vacuum patterns” (Gardner, Kent, Lai, Geddes, & Hartmann, 2019), researchers tested whether using a breast pump pattern that more closely mimics infant sucking (versus a standard 2-phase pumping pattern) would change the number or characteristics of milk ejections (i.e. letdowns) or milk removed. They recruited lactating mothers at various stages and measured, during pumping, how many ejections occurred, peak milk flow, and percent of available milk removed. They found no significant difference between the infant-derived pattern and standard pattern in the number or timing of milk ejections or in how much milk was removed. This suggests that the basic physiology of letdown is relatively robust—i.e. the pattern of hormone-driven ejections is not easily altered by small changes in external stimulus. Thus, while multiple letdowns do occur, they seem to follow an individual “preset” pattern that is fairly stable across different stimulation modalities. (Gardner et al., 2019) BioMed Central

In another classic (but still highly relevant) study, “Milk ejection patterns: an intra-individual comparison of breastfeeding and pumping” (Gardner, Ramsay, Hartmann et al., 2015), researchers used ultrasound and milk flow measurement to compare how milk ejection (letdowns) behaves when an infant breastfeeds versus when a mother uses a breast pump. They found that within individual mothers, the number, timing, and duration of milk ejections were quite consistent regardless of whether the breast was stimulated by a baby or by a pump. That is, a mother’s pattern of letdowns tends to be stable across modes of milk removal. (Gardner et al., 2015) PMC

Suggestions for lactation specialists

Recognize that multiple letdowns across a feed are normal, but the specific “schedule” of letdowns (how many, how spaced) is relatively stable per individual, and not easily changed by external tools or techniques.

When supporting pump users, acknowledge that optimizing flange fit, vacuum, and comfort is important—but also know that you may not be able to “force” additional letdowns beyond what the mother’s physiology naturally yields.

Emphasize consistency in feeding or pumping frequency: because letdown patterns are stable, ensuring regular removal is key to sustaining milk flow.

When teaching parents about letdown cues, frame them not as rigid signals but as helpful feedback—encourage observation of baby’s sucking/swallowing changes and reassure that absence of strong cues doesn’t always indicate a problem.

If a parent reports weak or delayed letdown, assess for impediments (stress, discomfort, nipple sensitivity) rather than assuming their physiology is wrong. Use supportive strategies to reduce inhibition (relaxation, comfortable environment) rather than trying to override physiology.

Key Terms & Definitions

Letdown Reflex: The letdown reflex is the natural process where oxytocin, a hormone released in the brain, signals the milk ducts to release milk. This reflex often happens when a baby latches and begins sucking, but it can also occur when a parent hears their baby cry or even thinks about their baby. Some parents describe a tingling or warm sensation in the breasts as milk begins to flow. For example, a mother might feel letdown start while watching a video of her baby. Understanding this reflex helps explain why milk sometimes leaks unexpectedly, especially in the early months of breastfeeding. It is the body’s way of ensuring milk is available whenever the baby needs it.

Milk Ejection: Milk ejection refers to the physical contraction of the small sacs in the breast, called alveoli, that push milk into the ducts so it can reach the nipple. This contraction is triggered by the letdown reflex and makes milk accessible to the baby. Without milk ejection, milk would remain stored in the alveoli instead of being delivered to the infant. For instance, when a baby sucks rhythmically, these contractions occur in waves to provide steady milk flow. Some mothers notice milk spraying when their baby unlatches suddenly, which is a clear sign of milk ejection. It is an essential step for efficient feeding and milk transfer.

Overactive Letdown: Overactive letdown happens when milk flows too forcefully, making it difficult for babies to coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing. Babies may choke, cough, or pull away from the breast during feeds. Parents sometimes notice milk spraying strongly if their baby unlatches, which can feel overwhelming to the infant. For example, a baby with an overactive letdown might gulp quickly and become gassy afterward. While this can be stressful, techniques like nursing in a laid-back position or expressing a little milk before latching can help. Recognizing overactive letdown helps parents and lactation consultants adjust feeding strategies to keep both baby and parent more comfortable.

Cues: Cues are signals that trigger the letdown reflex, preparing the body to release milk. These can be physical, such as nipple stimulation, or emotional, like hearing a baby cry or even thinking about feeding. Some parents experience letdown when they smell their baby’s blanket or hear another infant crying. These triggers show how closely the brain and body are connected during lactation. For example, pumping milk may be easier if a parent looks at photos or videos of their baby. Recognizing and using cues can make milk expression more efficient and feeding sessions smoother.

FAQs about the Let-Down Reflex (Milk Ejection Reflex)

-

Scenario: 3-day postpartum parent who never feels tingles or pins-and-needles.

Answer: Many people never feel let-down, and that’s normal. Look instead for signs: baby’s sucking changes from quick “flutter” sucks to slow, deep swallows; you hear rhythmic gulping; milk appears in the pump; or the other breast leaks. If baby has 6+ wet diapers after day 5, steady weight gain, and softening breasts after feeds, your let-down is happening. -

Scenario: 2-week-old sputters at the start of feeds; parent feels a strong spray.

Answer: That’s often a fast let-down. Try laid-back (reclined) nursing so gravity slows flow, or start with hand-expressing/pumping 1–2 minutes before latching. Offer one breast per feed (“block feeding” only with guidance), burp after the initial fast flow, and let baby pause as needed. Most babies adapt within weeks. -

Scenario: At a noisy family gathering, it takes 5–8 minutes for milk to flow.

Answer: Stress hormones can blunt oxytocin release. Build a short pre-feed routine: deep belly breaths (4 in/6 out for 2 minutes), shoulder rolls, warmth on the breast, a sip of water, and looking at baby photos/video. A quiet corner or noise-canceling headphones can help. Consistency usually shortens time-to-let-down. -

Scenario: Back at work, the pump yields little the first 5 minutes.

Answer: Use your pump’s let-down mode (fast/light suction) for ~1–2 minutes, then switch to expression (slower/stronger). Watch a baby video, smell a worn baby onesie, or do a 60–90 second warm breast massage before pumping. Correct flange size (nipple moves freely, minimal areola pulled) protects oxytocin release and yield. -

Scenario: Around 3 months, tingling fades and breasts feel softer.

Answer: Supply and let-down often feel subtler as your body regulates. Softer breasts aren’t low supply if diapers/weight are normal. Babies also get more efficient. If diapers drop, feeds shorten drastically with fewer swallows, or weight gain slows, get a weight check and a latch/pump assessment.

All About Breastmilk Letdowns | What is the milk ejection reflex?

👉 Knowledge Check

-

Breast structure & function. Think of the breast as a small factory with pipes. Milk-making sacs (tiny clusters) produce milk, and small tubes carry it to the nipple. Tiny squeezing cells push milk along. A deep, comfortable latch—baby’s chin pressed to the breast, wide open mouth, rounded cheeks—lets milk flow well and prevents sore nipples.

Hormonal regulation. In late pregnancy the breast makes small amounts of colostrum. After the placenta is delivered, milk volume rises around days 2–4. Two main messengers run the show: prolactin tells the body to make milk, and oxytocin helps release milk. From then on, supply follows use: milk that is removed often (8–12 times in 24 hours) tells the body to make more; milk that sits in the breast tells it to slow down.

Let-down (milk ejection) reflex. When the nipple is stimulated, a signal goes to the brain and oxytocin is released, causing waves of milk to let down. Some parents feel tingling or a sudden rush; it can happen several times in one feed. Let-down is helped by skin-to-skin, warmth, gentle breast massage, and relaxed breathing, and it can be blocked by pain, stress, nicotine, tight clothing, or some medicines—so reduce those barriers first.

-

Geddes, D. T., & Sakalidis, V. S. (2016). Sucking dynamics of breastfeeding infants. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 21(3), 134–139. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1744165X16300217

Kent, J. C., Gardner, H., & Geddes, D. T. (2016). Breastmilk production in the first 4 weeks after birth of term infants. Nutrients, 8(12), 756. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/8/12/756

Neville, M. C., & Morton, J. (2001). Physiology and endocrine changes underlying human lactogenesis and milk secretion. The Journal of Nutrition, 131(11), 3005S–3008S. https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/131/11/3005S/4686950

Ramsay, D. T., Kent, J. C., Hartmann, R. A., & Hartmann, P. E. (2005). Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. Journal of Anatomy, 206(6), 525–534. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00426.x

Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Prime, D. K., & Geddes, D. T. (2019). Oxytocin effects in mothers and infants during breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica, 108(6), 1033–1044. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/apa.14745

Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J. D., França, G. V. A., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)01024-7/fulltext

World Health Organization. (2009). Infant and young child feeding: Model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals (WHO/UNICEF). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44117

Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2018). ABM Clinical Protocol #9: Use of galactogogues in initiating or augmenting maternal milk production, with cautionary note (Revised)—PDF. https://abm.memberclicks.net/assets/DOCUMENTS/PROTOCOLS/9-galactogogues-protocol-english.pdf

Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2020). ABM Clinical Protocol #32: Hyperlactation—Diagnosis, management, and prevention—PDF. https://abm.memberclicks.net/assets/DOCUMENTS/PROTOCOLS/32-hyperlactation-protocol-english.pdf

Wambach, K., & Spencer, B. (2021). Breastfeeding and human lactation (6th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. https://www.jblearning.com/catalog/productdetails/9781284223127

Lawrence, R. A., & Lawrence, R. M. (2021). Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical profession (9th ed.). Elsevier. https://www.elsevier.com/books/breastfeeding/9780323680137